The Non-Intrusion Conflict.

It was in the autumn of that same year (1834), that

the important parish of Auchterarder, pleasantly situated at the foot of

the Ochils, became vacant, and Lord Kinnoul, the patron, on the 14th of

October, presented to the living, Mr. Robert Young, a preacher of the Gospel.

The people had the usual opportunity of testing his ministerial qualifications,

but their opinion was so adverse, that out of a population of 3000, only two

individuas, Michael Tod and Peter Clark, could be found to express approbation

by signing the call. Five-sixths of the congregation, on the other hand, came

forward solemnly to protest against his settlement. The Church, accordingly,

found that they could not proceed to his ordination at Auchterarder, and the

patron was requested to make another appointment.

|

Unfortunately, this was not done. Lord Kinnoul and his presentee resolved to carry the case into the Civil Courts, and after the usual preliminary delays, the pleadings began in November, 1837. On the 8th of March, the sentence of the Court was pronounced adverse to the Church and the Christian people. It was decreed that in the settlement of pastors the Church must have no regard to the feelings of the congregation. The trials of the presentee must be proceeded with in order to ordination, just as if the refusal of the people had not been given. |

To ward off if possible, from the Established Church the consequences of

this decision, the case was appealed to the House of Lords, where the pleadings

were heard in March, 1839, and the decision given on 2nd May of that year. The

sentence of the Scottish Court was confirmed. The wishes of Christian

congregations were to be considered of no value in any way, and Lord Brougham,

in order to make his meaning plain, introduced a simile which attracted much

attention in Scotland. Alluding to the fact that when the Sovereign of Britain

is crowned in Westminster Abbey, one of the coronation ceremonies is the

appearance of a champion on horseback, his Lordship remarked that as no one

could suppose that the recalcitration of the champion's horse could invalidate

the act of coronation, so the protest of a reluctant congregation against an

unacceptable presentee would be equally unavailing. The solemnly declared

judgment of a Christian congregation would have as little value as the kick of

the champion's horse.

Such a decision, so explained, was sufficiently

startling; but as if to make the matter yet more plain, the case of

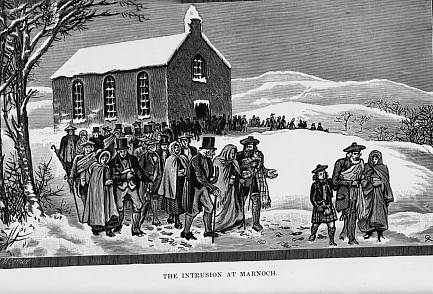

Auchterarder was followed by those of Lethendy and Marnoch.(See

picture above of the "Intrusion at Marnoch") At Lethendy the people had

rejected Mr. Clark, the presentee, an unhappy man, who subsequently gave

himself up to drunkenness. The patron and the Presbytery had agreed to settle,

and actually did settle, another preacher in the pastoral charge; but Mr. Clark

dragged the Presbytery into the Court of Session, when certain proceedings took

place to which we shall afterwards refer. The case of Marnoch,

Strathbogie, deserves special attention. It was in 1837 that the vacancy

occurred, and Mr. Edwards, a preacher of the Gospel, was presented to the

living. For three years he had officiated in the church as assistant to the

former minister, and the parishioners knew him only too well; so well, that

only one man, Peter Taylor, the innkeeper, signed his call, while six-sevenths

of the congregation actively opposed, his settlement. In May, 1838, he was set

aside by the Church. As in the former cases, Mr. Edwards appealed to the Civil

Courts, and in June, 1839, a decision was given to the same effect as before.

No regard was to be had to any opinions or feelings of the parishioners. At

Marnoch, however, a new feature came into view. The majority of the Presbytery

belonged to that party of Moderates in the Church who agreed with the Civil

Courts in wishing to retain the power of intruding presentees on unwilling

congregations; and so, when the Court of Session ordered the settlement of Mr.

Edwards to go forward, they readily lent themselves to the work The supreme

Courts of the Church were obliged to interfere, and this they did in the most

decisive way. At the rising of the Assembly in 1839, the Commission of that

Court expressly prohibited the Presbytery of Strathbogie from taking any steps

towards the settlement of Mr. Edwards. It soon appeared, however, that the

majority of that Court were resolved to ignore the prohibition; and this having

been formally brought before the Commission at its next meeting, the Moderate

majority of the Presbytery were suspended from their office as ministers of the

Church, and prohibited from all acts, ministerial or judicial. This was done

because they would give no promise to refrain from the intrusion of Mr.

Edwards, and because the Church was resolved to protect the people from such

intrusion. It might have been expected that ministers of the Gospel, who had at

their ordination vowed obedience to their ecclesiastical superiors, would have

respected their vows. But their desire to obey the Court of Session, and carry

out the forced settlement, prevailed. In breach of their sacred engagements,

they resolved to meet at Marnoch on the 21st of January, 1841; and the striking

scene which then took place will not soon be forgotten. The snows of mid-winter

lay deep on the ground, but when the seven Strathbogie ministers met at the

church, 2000 people were gathered around and within it. No sooner had the

pretended Presbytery taken their places than a solemn protest was handed in by

the parishioners against the deed that was about to be done. "We earnestly

beg you . . . to avoid the desecration of the ordinance of ordination under the

circrunstances; but if you shall disregard this representation, we do solemnly,

and as in the presence of the great and only Head of the Church, the Lord Jesus

Christ, repudiate and disown the pretended ordination of Mr. Edwards, and his

pretended settlement as minister of Marnoch. We deliberately declare that, if

such proceedings could have any effect, they must involve the most heinous

guilt and fearful responsibility in reference to the dishonour done to

religion, and the cruel injury to the spiritual interests of a united Christian

congregation." Having delivered this protest, it was intimated the people

would leave them to force a minister on the parish, with scarcely one of the

parishioners to witness the deed.

| The scene that followed was indeed touching and impressive. In a body the parishioners rose, and, gathering up the Bibles" which some of them had been wont to leave, for long yeam. from Sabbath to Sabbath in the pews, they silently retired. "The deep emotion that prevailed among them was visible in the tears which might be seen trickling down many an old man s cheek, and in the flush, more of sorrow than of anger, that reddened many a younger man s brow. ‘We never witnessed, said an onlooker,* ‘a scene bearing the slightest resemblance to this protest of the people, or approaching in the slightest degree to the moral beauty of their withdrawal; for, stern though its features were, they were also sublime. No word of disrespect or reproach escaped them; they went away in a strong conviction that their cause was with the Most Powerful, and that with Him rested the redress of all their wrong. Even the callous-hearted people that sat in the pew, the only pew representing intrusionism and forced settlements, were moved—they were awed; and the hearts of some of them appeared to give way. |  Scene drawn after the Disruption

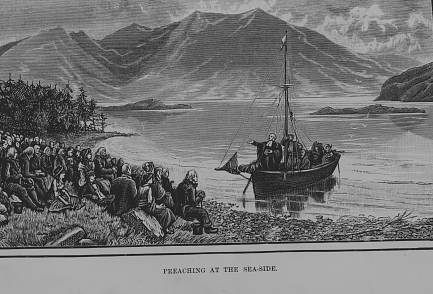

showing a typical Sabbath in the glen - preaching in the open being necessary

after the thrusting out described above. Scene drawn after the Disruption

showing a typical Sabbath in the glen - preaching in the open being necessary

after the thrusting out described above. |

"Will they all leave?" we heard some of them whispering. Yes; they all

left, never to return until the temple is purified again, and the buyers and

sellers - the traffickers in religion - are driven from the house of God. THEY

ALL LEFT.(Quote from the Aberdeen Banner newspaper)

In this way it was that

the course of events did more than anything else to open men's eyes to the

great principle of Nonintrusion. During the whole of the Church's history it

had been held that the call of the people was essential before a minister could

be settled. The congregation must invite before the Presbytery could ordain.

Here were cases, however, one after another, in which the parishioners were

virtually unanimous in their opposition to the presentee. Was the call, then,

to be treated as a mockery? Were the Michael Tods and the Peter Taylors of

Scotland to overbear the whole Christian people of united parishes? Was it to

be tolerated that the members of Christian congregations must submit to have

obnoxious preseutees forced on them? Surely it is not to be wondered at that so

large a body of the ministers and members of the Church should have felt that

these proceedings could not be in accordance with the mind of Christ, and

should have determined that in such settlements they must at all hazards refuse

to take part.