Scripture Characters -

for the Young.

CHAPTER I.

THE HEBREW MAID.

2 KINGS v. 3.

ISRAEL was now in a state of much depression and weakness,

because of the general apostasy of its people from the service and worship of

the true God. And Syria, on its northern borders, was the common instrument of

its humiliation and chastisement.

In one of the frequent forays which

marauding companies of Syrians had made into the land for purposes of insult

and plunder, they had carried away captive, a little Israelitish maiden, who

appears to have belonged to one of the few families that in the midst of

wide-spread degeneracy, had remained faithful to the God of their fathers.

Perhaps, in the division of the spoils on their return, she had been allotted

to Syrian household in which we find her. Or we imagine the beautiful and timid

captive exposed in the crowded slave-market of Damascus, and way becoming a

domestic attendant upon the of Naaman the Syrian.

This man,

distinguished for personal valour and for signal military successes which had

made the whole land his debtor, was the commander-in-chief of the armies of

Syria, and the confidential adviser of his king, to whom he stood nearest in

rank and power. It is natural to picture him as living in a palace, in the

midst of one of those orchards of apricots, pomegranates, and other trees

which, for three thousand years, have made Damascus the garden of the East. But

what embittered all his enjoyments, and withered all the beauty of the paradise

by which he was surrounded, was the fact that he was afflicted with the

terrible and loathsome disease of leprosy, so that, as good Bishop Hall has

quaintly said, ' the basest slave in all Syria would not have changed skins

with Naaman, had he gotten his office to boot'

He appears to have been a

man of much natural generosity, and to have treated the little captive girl so

kindly as to have gradually won her confidence and awakened her sympathy; so

that, while she did not forget her own kindred and her father's house, and was

no stranger to home-sickness, she gradually became, in some degree, reconciled

to her captivity. It was not easy for the natural hope and buoyancy of so young

a heart, to continue habitually repressed ; and, like the caged bird, she could

sing at times even in her bondage.

We may conceive her to have looked on

at first with affectionate but silent interest, to have seen the agents of

superstition trying all their charms, and the native physicians exhausting all

their skill upon her master, in vain; for still the fatal malady, which her

Hebrew education had taught her to regard with peculiar dread and aversion,

made steady progress, consuming his strength and 'wasting his beauty like a

moth' and threatened soon to turn that splendid mansion into a house of

mourning. Waiting from day to day upon her mistress, she read in her

countenance the darkening signs of anxiety and sorrow; and unable at length to

repress the thoughts which had often risen in her mind, with affectionate

artlessness she one day dropped the kind hint: 'Would God my lord were with the

prophet that is in Samaria! He would recover him of his leprosy.'

Here

was a gleam of light in the midst of the thickening gloom. Her mistress reports

the words of the little maiden to her husband ; and as the dying man hears

them, he once more begins to hope for life. Further inquiry increases the hope;

and he resolves that he will try this one additional means for

recovery.

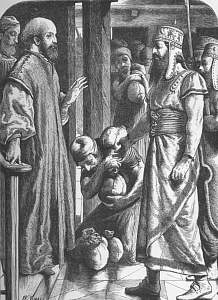

We know from the later portions of the narrative how it sped

with Naaman. Hastening into Samaria with a numerous retinue suited to his rank,

with pieces of gold, and talents of silver, and changes of raiment for

presents, the snowy peaks of Lebanon soon rose between him and his native

Syria. He waited in his chariot at the door of the prophet Elisha. And the

result was, that he was not only delivered from his leprosy but from his

idolatry, that he obtained in one day both health and salvation, and returned

rejoicing to his own land, a worshipper and servant of the only living and true

God who made the heavens and the earth.

Now we may look at this story,

in its incidents and issues, in two lights,—in the illustrations which it

gives us of the manner in which God made known His name and vindicated His

glory, in those times, among heathen nations; and in the general principles and

lessons for all times which it suggests.

I. Viewing it for a

little in the former of these aspects, we may take occasion from it to correct

the mistaken opinion into which some have fallen respecting the exclusive

nature of the ancient Judaism.

One would be led to suppose from the

representations which some have given, that the sacred land was surrounded by a

wall of brass a hundred feet high, and that the utmost jealousy was shown of

any of the rays of that divine light which had been communicated to the chosen

people, being permitted to pass beyond it. This is so great an exaggeration of

the actual facts, as in effect to amount to a serious error.

The Jewish

Church, when it fulfilled its proper mission, was the guardian of Heaven's

truth, not its monopolist or its jailer. Its peculiar institutions and

observances were framed and appointed, not for the purpose of preventing truth

from passing out, but of preventing corruption and error from coming in. At all

times winged seeds of truth were finding their way into heathen lands, striking

roots downward and bearing fruit upward, as now in the case of this young

Hebrew captive in the house of her Syrian lord. In this respect, as well as in

the ordinances of nature in which God ' gave to men rain and fruitful seasons,'

He never 'left himself in those nations ' without a witness.'

The

numerous colonies of Jews too, migrating to the various Gentile cities and

erecting synagogues there, ages before the advent of Christ, became, on a

grander scale and in a more systematic and imposing manner, witnesses for God

and pioneers of the gospel of the kingdom. The gate of the ancient Church,

covered over with its mystic scrolls and pictorial emblems, stood open day and

night, to every Gentile who was willing to enter it as a proselyte. And the

court of the Gentiles in the Jewish temple was the perpetual and designed

recognition of this truth, which Jesus, by driving out from it the

money-changers and the sellers of doves who crowded and polluted it, anew

restored and proclaimed.

And there is more in regard to the manner of

God's manifesting His name and declaring His supremacy and glory before the

heathen, of which these incidents afford impressive illustration. It is to be

remembered that, when the Jews revolted into idolatry and its accompanying

vices, they ceased to fulfil their high and peculiar mission as the chosen

people, and to be witnesses for God before the other kingdoms of the earth. And

more than this, when they were allowed to fall into subjection to the heathen,

and to be grievously oppressed and punished by them,- which was the case as

often as they apostatized,- their heathen oppressors were only too ready to

conclude, not only that they had subdued the Israelites, but I that their gods

had prevailed against the God in whom the Israelites trusted. But no one can

have read with proper reflection the inspired history of the Jewish people,

without observing the many occasions in which, when this was their condition,

God interposed in a remarkable manner to assert and vindicate His sovereignty,

and to cast shame upon all those vanities and dumb idols in which the heathen

put their trust, compelling the very idolaters to confess, like the Baal

worshippers of Elijah's times at the sublime trial on Mount Carmel, 'Jehovah,

He is the God,- Jehovah, He is the God.'

I consider the series of

incidents, in which this little Israelitish maiden unconsciously bore so

important a part, as belonging to the class of facts to which I have now

referred; and I do not think that the transaction is regarded in its true

significance, or in some of the principal designs for which it has been placed

on permanent record in the sacred volume, until this is clearly observed by us.

God was now vindicating His supremacy and awful majesty and power in the sight

of the heathen nations, and especially of the proud Syrian people, when the

degenerate Israelites had become unfaithful to their high commission. And when

we consider that Naaman was the great military chief and defender of Syria, his

power casting its shadow upon the throne of Ben-hadad himself, that all the

resources of his false gods had been impotent for his cure, and that any

deliverance of which he might become the subject would awaken the wonder and

the joy of all Syria, it is easy to see how admirably and singularly fitted his

cure by the prophet of God in Samaria, to whom this little Hebrew captive now

sent him, was, in all its circumstances, to vindicate the divine glory and

supremacy.

II. We have placed these remarks in the foreground,

because we consider them necessary to the proper understanding of this passage

of inspired biography. But there are general principles and lessons for all

time suggested by it which we now proceed to indicate, and which may render the

words of the Hebrew maiden, which were as life from the dead to Naaman,

profitable for us also.

I. We scarcely know of any fact

recorded in Scripture that more beautifully illustrates the value and influence

of early religious instruction.

In those good words spoken in season,

and with such artless simplicity, by the young Israelite, she was giving forth

the impressions and the lessons of her childhood for the benefit of her Syrian

lord. She remembered well a venerable man, clothed in a prophet's mantle, who

held communications with the true God and delivered His awful messages to men.

She knew that, in the name and by the power of that God in whom he trusted, he

had wrought many miracles of benevolent power, and that in one memorable

instance he had even raised the dead. And although her master was not an

Israelite, yet, such was her confidence in the power and compassion of the God

of her fathers, that she could not doubt, if he sought His healing mercy by the

hands of His prophet, that he would not be allowed to seek it in vain. All the

blighting influences of the surrounding heathenism had not been able to destroy

these hallowed memories, or to wither these holy faiths in her young heart We

hear the well-trained Israelite in every word that she utters: ' Would God my

lord were with the prophet that is in Samaria, for he would recover him of his

leprosy.'

We are not expressly told whose hands had sown those precious

seeds of early instruction in the heart of this little captive girl. But most

probably it was those of her own parents, who had many a time been praying,

since she was torn from them, that, if she still lived, she might not forget,

in that land of idolaters, the God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob. And now that

she is in the midst of heathen people, and there is no parent's hand to fan the

spark of her early piety, those lessons of her childhood begin to drop with

fruits of inestimable price.

It has sometimes happened that religious

instructions, which appeared to leave no marked impression at the moment, have

begun to germinate in future years and in foreign lands. The gathered fuel upon

the altar has been suddenly wrapt in a living flame by fire from heaven. It is

a fine thought of the poet-philosopher Richter, that the first colours that are

painted on the mind are usually immortal. The first mountain that we have seen,

the first strain of music that we have heard, the first look that we have had

of the solemn sea, are never forgotten.

Ply then your blessed work, ye

who are parents. You now paint in undying colours. Your work shall have eternal

issues. From a child let your little ones 'know the Holy Scriptures, which are

able to make them wise unto salvation, through faith which is in Christ

Jesus.'

' The clay is moist and soft; now, now, make haste, And form the

pitcher, for the wheel runs fast.'

2. And surely the

words before us, with their consequences, were meant to tell us of the power

for good that is possessed by persons even in the most unfavourable stations in

life.

Had we been asked to represent beforehand the case of an

individual who should be almost powerless for good - a withered leaf made to be

the sport of winds - a passive waif floating down the stream of events, but

utterly unable to control them - a human being not even entrusted with one

solitary talent with which she might trade for God - we should probably have

described circumstances not greatly dissimilar to those in which this young

Hebrew maiden was situated. Was she not young and friendless - a stranger in a

foreign land, a poor captive in the mansion of a rich Syrian lord? And yet even

she was able to drop a word, which changed the whole current of her master's

life, took the gall and poison out of his earthly cup, and, there is good cause

to think, brought him to the blessed knowledge of the true God. She had a

little light, and she made it shine, and lo, it gave light unto all who were in

the house!

Who can tell the history of a sentence, or even a word! It

may awaken echoes that shall reverberate and multiply and deepen through all

time. How far-reaching were the consequences of this one sentence so sincerely

and lovingly spoken! Her 'wholesome tongue became a tree of life,' and it was

shown that 'life and death were in the power of it.' What human being may

presume that he is independent of his neighbour, or knows from what hand help

in his time of need may come to him? 'The eye cannot say to the hand, I have no

need of thee; or the hand to the foot, I have no need of thee.' There is as

much of true philosophy as of beauty in those words of the poet, when he says

that even

'The daisy, by the shadow that it casts,

Protects the

lingering dew-drop from the sun.'

What the greater number of us want

is, not so much talent and opportunity, as an honest and earnest desire and aim

to do good. Occasions are presenting themselves to the most obscure among us a

hundred times every day. Men of science tell us that there is no waste of power

in nature, but even the gossamer-web of the insect, and the falling leaves of

autumn, and the snow-flakes of winter, have their appointed uses in the great

laboratory of the earth. But just as little is it true in the moral world that

any human being is condemned to uselessness. You do not even need to step out

of your own sphere, or to join a benevolent society, in order to benefit your

fellow-men. The story of the poor widow in the island of Rona, who was

accustomed on stormy nights to place a lighted candle in her window at the

entrance to the dangerous harbour, in order to guide homewards the fishermen

who were out toiling in the tempest, shows us that those who seem the most

unfavourably situated, may yet do some service for others, if they have but the

heart for it; while the example of this Hebrew captive, out of whose mouth God

now perfected strength, may shut the lips of apologists for indolence to the

end of the world. Nay, it often happens that one good act has hidden in its

bosom the germ of others, and multiplies and enlarges itself many times in

blessing.

'A grain of corn, an infant's hand

May plant upon an inch

of land,

Whence twenty stalks may spring, and yield

Enough to stock a

little field.

The harvest of that field might then

Be multiplied to ten

times ten ;

Which sown thrice more, would furnish bread

Wherewith an army

might be fed.'

3. We may also see in the language and

conduct of this young Israelite, a noble example of fidelity to the honour of

her religion.

Many in her own land had been recreant to their faith, and had

gone aside to the worship of strange gods. But here, in this land of strangers,

among the worshippers of Rimmon and the oppressors of her race, she lifts her

little hand in solitary and fearless protest for the living God and the true

worship. For there is every reason to think, that she had silently waited until

her distressed master had tried and exhausted all the resources of Syrian

skill, and all the blind appliances of Syrian superstition, before she gave

utterance to her devout and kindly wish. And therefore, in the circumstances,

her words were equivalent to saying, ' The gods of Syria can do nothing to heal

my leprous master; they are dumb idols all, having eyes but seeing not, and

ears but hearing not; and they that make them are like unto them ; so are all

they that put their trust in them. But my God and the God of my fathers,

through the instrumentality of His prophet, both can and will. Would God my

lord were with the prophet that is in Samaria! for he would recover him of his

leprosy.'

What faith and courage were in this language! In this little

captive maiden there were the germs of which God makes His martyrs.

But

what a loud rebuke does her behaviour pronounce upon those who, while in public

profession they have named the name of Christ, are slow to confess Him before

His enemies, to defend His institutions, His doctrines, and His laws! They

delight in circles from which all reference to the Lord that bought them is

formally excluded, or where the mention of His name would be a jarring note.

The world speaks loudly in their presence of its idols ; but they are content

to be silent about their divine Saviour. The reason of their guilty cowardice

is to be found in the want of qualities which this young Israelite possessed.

There was consistency between her life and her religious profession, and this

gave her holy boldness. And then her religious convictions were firm and deep,

and it is the full vessel that overflows. It was a little truth that she knew,

but she believed it with all her heart; and there is more of moral influence

from a little portion of truth strongly believed and held as with a life-grasp,

than from a larger measure of truth that is regarded only with a kind of half

faith. Persons like this Hebrew maiden rise above fear; they must speak ' out

of the abundance of their heart,' and tell those who need to be told it, that

'there is balm in Gilead, and a Physician there.'

4. We

may also notice in this young Israelite, an example of some of the essential

qualities of a good servant.

She did not allow herself to pine away in

sullen discontent, as her captivity might perhaps have seemed to some to

justify. She did not fall into the selfish mistake of imagining that her own

interests and those of her master were different and even opposite. Nor did she

measure out her service according to the hireling principle of so much wages on

the one hand, and so much work on the other. But the true-hearted maiden took a

sincere interest in the well-being of the family in which her lot was cast,

identified herself with it, lovingly sought its good; and we hear this feeling

now breathing itself out, in the time of family distress, in this affectionate

wish' Would God my lord were with the prophet that is in Samaria, for he would

recover him of his leprosy.'

In every properly regulated household, the

interest will be reciprocal. There will be a sympathetic chord passing from the

humblest to the highest, and from the highest to the humblest: the master will

conscientiously care for the good of those who are placed for the time under

his domestic rule; and the Christian servant, who carries her principles

consistently into this relation, will make the prosperity of the family in

which she lives her own,- thinking for it, praying for it, weeping when it

weeps, and rejoicing when it rejoices.

How finely did the conduct of the

good Eliezer of Damascus, Abraham's servant, exemplify the same spirit, when he

was sent forth on the peculiarly delicate and important mission of obtaining a

wife for his master's son! With what anxiety did he guard at every point his

master's honour! With what thoughtful plan did he always seek to do the best

thing in the best way, and at the best time ! How devoutly did he watch and

mark the leadings at once of conscience and of Providence! How thoroughly did

he put his mind and heart into every step and stage of the enterprise! And with

what honest and sincerely religious joy did he delight and give thanks to God,

when success at length crowned his undertaking, and he bore the beautiful and

modest bride home to Isaac!

I am well aware, how much the existence of

this happy state of things in a household depends upon right principles, and

proper treatment, on the part of the master or mistress to the servant; and

that many a servant has at length become a hireling through being treated as a

hireling, and, in consequence of being always regarded with suspicion, has come

to deserve to be suspected. But where you persevere in 'showing all good

fidelity' you will generally succeed at last in winning both confidence and

esteem ; and, moreover, the undutifulness of others, while it makes our

discharge of duty more difficult, does not excuse us from it. The Christian

servant in an ungodly household should remember, that there especially she is

the representative of her religion, and should aim to show, like this Hebrew

maiden in the house of Naaman, and like Onesimus in the house of Philemon, that

her religion has ' made her profitable.' There is a Master in heaven 'by whom

actions are weighed ;' and love to Him makes the wheels of obedience move

easily and sweetly, and invests obedience itself with a new quality and a new

preciousness.

A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine :

Who sweeps a room, as for Thy laws,

Makes that and th' action

fine.

This is the famous stone

That turneth all to gold :

For

that which God doth touch and own

Cannot for lesse be told.'

5. I must not bring to a close my remarks on the story of this Hebrew

maiden, without noticing the singularly impressive illustration which it

affords of the wondrous operation of divine providence in educing good from

seeming, and even from real, evil. How strangely had God linked the destinies

of these two human beings together,- the Israelitish slave and the Syrian

chief! To her young heart it must have appeared a sad calamity, to be torn in

her childhood from her beloved Hebrew home on the banks of the Jordan, and to

become a domestic slave in a heathen's family. But God had brought her hither

for great ends, even that she might lead her master as a trophy to His feet,

and make all Syria resound with the confession, that ' there was no God like

unto the God of Jeshurun.'

And then, what did Naaman's leprosy appear to

him and to all that looked on him, but the dark shadow cast upon his otherwise

prosperous life, the drop of bitter which turned everything to. wormwood, the

skeleton in the house ever pointing with its bony finger to an opening grave ?

While, all along, this terrible providence had been bearing in its bosom, his

greatest mercy, and was to prove a primary link in that golden chain of events,

by which he was to be translated from the kingdom of darkness into the kingdom

of God.

We are poor judges of what is to be the issue of events, and

often tremble and even murmur when we should adore. The dark-winged messenger

came from heaven with healing in its wings. When the Lord is coming to bless

us, and to hold closer communion,with us, He often comes still, walking on the

stormy wave, and, looking at Him through the mist and gloom, we mistake the

kind Saviour for an angry spectre.

Go To Chapter

Two

Home | Links | Literature |

Biography